No beating around the bush, we will be jumping straight in it.

The Iterator Trait

In Rust, an iterator is basically a type that knows how to yield items one at a time. We will take the example of a vending machine and its items (like snacks) to understand how it works. So an iterator is like a vending machine which yields a packet of snacks one at a time.

So everytime, .next() is hit on an iterator, the next item is given if available else None is returned (snacks are exhausted). The snack is given out till the machine is empty.

So something which implements the Iterator trait is called an iterator.

rustpub trait Iterator { type Item; fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item>; //there are many other methods implemented here }

type Item defines what the iterator will yield (e.g. i32, String, etc.)

To understand it better, let us build an iterator from scratch

ruststruct Counter { current: u32, }

This counter should count from 0 to 4 and then return None after that. The implementation looks very simple.

rustimpl Iterator for Counter { type Item = u32; fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> { if self.current < 5 { let result = self.current; self.current += 1; Some(result) } else { None } } }

The Item which will be yielded by our Counter iterator will be of type u32. We check if the current count is less than 5 and then return count + 1 else we return None. We can run a simple for loop to test our implementation.

rustfor x in Counter { current: 0 } { println!("{x}"); }

And we get numbers from 0 to 4 printed nicely (not yet as .into_iter is not here). This looks neat but the iterator trait we implemented on our struct gets invoked implicitly. It desugars this into raw trait calls. So what happens under the hood?

rustlet mut iter = Counter { current: 0 }.into_iter(); // uses IntoIterator (we'll discuss it later) while let Some(x) = iter.next() { println!("{x}"); }

Rust doesn’t assume you're passing an iterator. You could be passing a Vec, &Vec, or some other iterable. So it calls .into_iter() to get an actual Iterator. Then we keep calling .next() until it returns None.

So how does the for loop work even when we only implemented Iterator on Counter?

IntoIterator trait

That’s where the IntoIterator trait comes in. When you write a for loop, Rust calls .into_iter() under the hood to turn your type into something it can loop over.

Let’s see what this trait looks like:

Let’s look into IntoIterator trait and see how into_iter() works. This trait converts a type into something that can be iterated over.

rustpub trait IntoIterator{ type Item; type IntoIter: Iterator<Item = Self::Item>; fn into_iter(self) -> Self::IntoIter; }

The syntax looks a bit painful but let’s go through what it translates into.

-

This trait converts a type into something that can be iterated over

-

It owns or borrows the data and returns an

Iterator -

It’s used by

forloops and by calling.into_iter()directly

This line type IntoIter: Iterator<Item = Self::Item>; Hey, the associated type IntoIter must implement the Iterator trait… and the Item of that Iterator must be the same type as Self::Item.

So, if our type implements IntoIterator, our type is “for-loop friendly”.

Let’s implement IntoIterator for our Counter struct.

rustimpl IntoIterator for Counter { type Item = u32; type IntoIter = Counter; //must implement Iterator with Item type same as Self::Item fn into_iter(self) -> Self::IntoIter { self } }

So we are telling the compiler compiler how to .into_iter() a Counter and that will return … another Counter.

Let’s Dissect it a bit

type Item = u32;

It is same as the Item from our Iterator impl. It ensures consistency:

Whatever our IntoIter returns must match the item type the for loop expects.

type IntoIter = Counter;

This tells Rust that the actual iterator you get from calling .into_iter() on a Counter is... itself!

Yes, the struct is its own iterator. That’s perfectly legal and common.

fn into_iter(self) -> Self::IntoIter { self }

We're saying:

"Hey Rust, just take self and treat it as an iterator. No conversion and no fuss."

Why does this work? Because we’ve already implemented Iterator for Counter. So once the for-loop gets the value via .into_iter(), it starts calling .next() on it.

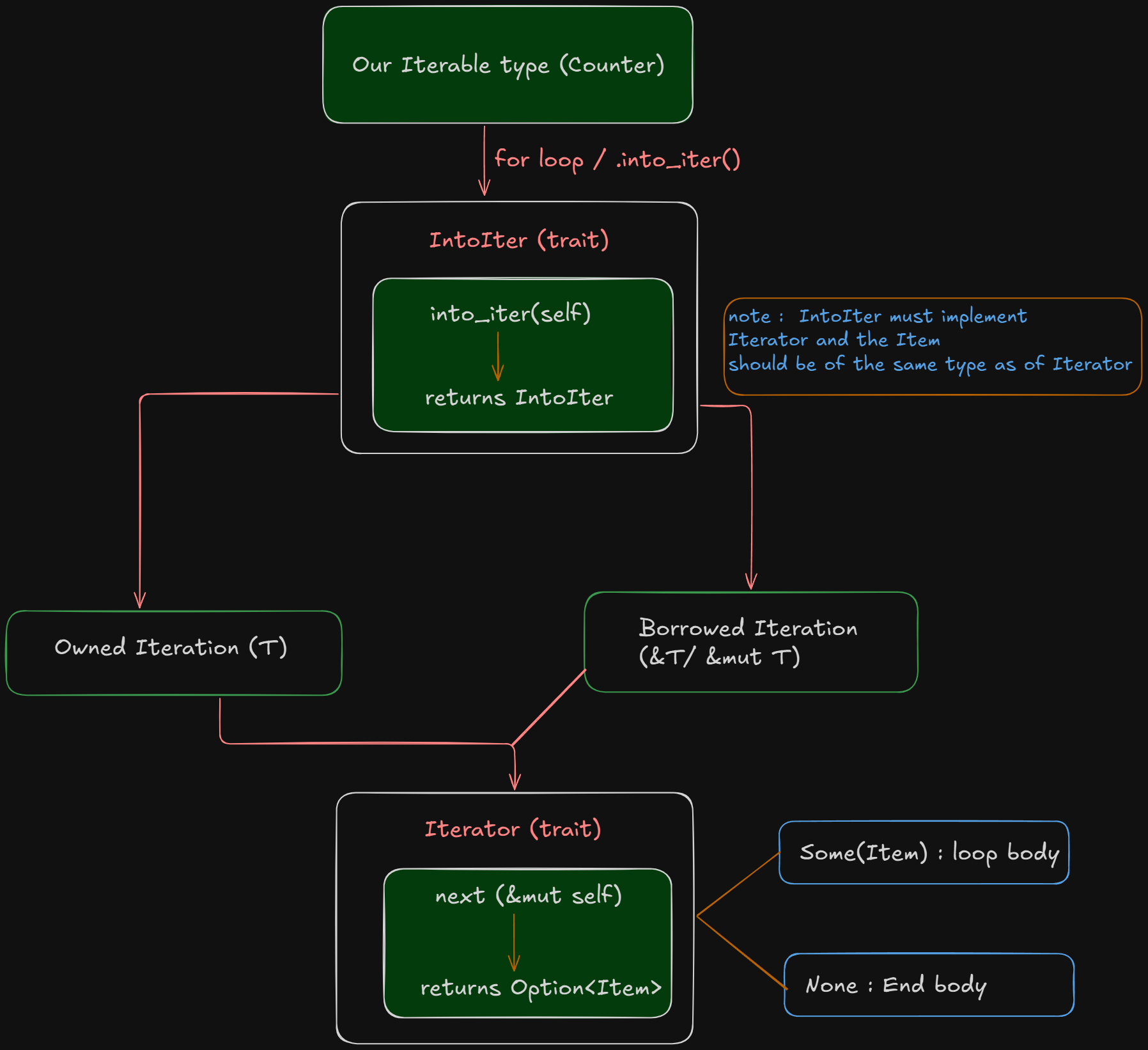

It kind of makes sense, but these things are roaming in the head in a very jumbled fashion. Let’s summarize the flow.

We needed IntoIter trait for the Counter struct to convert itself into something that implements Iterator. The .into_iter() method on Counter returns an iterator type (Counter itself) that actually implements Iterator and defines how items are yielded using .next().

This thing should now fit into the slot perfectly. Let’s take this diagram as an aid to put out the whole iterator flow at a place.

Iterator Ergonomics

We have already built a struct, implemented Iterator, then wrapped it with IntoIterator. That’s the custom path. Now let’s actually understand how Rust’s built-in types like Vec<T> give you super clean iterator ergonomics using three flavors of IntoIterator.

There are 3 flavors of iteration. Let’s look at a canonical example.

rustlet v = vec![1, 2, 3]; for val in v { // v.into_iter() -> ownership for val in &v { // (&v).into_iter() -> shared borrow for val in &mut v { // (&mut v).into_iter() -> mutable borrow

Behind the scenes, something like this is happening.

rustIntoIterator::into_iter(v); IntoIterator::into_iter(&v); IntoIterator::into_iter(&mut v); //all are called inside the while loop like before

Which means that the Vec<T> implements IntoIterator for all 3 forms:

rustimpl<T> IntoIterator for Vec<T> // owned impl<'a, T> IntoIterator for &'a Vec<T> // shared ref impl<'a, T> IntoIterator for &'a mut Vec<T> // mutable ref

.iter() and .iter_mut()

Just like IntoIterator for Counter gives up .into_iter() style

-

IntoIterator for &Countergives us.iter()style -

IntoIterator for &mut Countergives us.iter_mut()style

So, it is very simple to implement the IntoIterator trait for these types as well. By doing so, you're giving users the full ergonomic experience of iteration, letting them decide whether to consume, borrow, or mutate, just like they do with built-in collections.

Let us impl the trait for &Counter and &mut Counter then. (we’ll breeze through this).

ruststruct CounterIter<'a> { counter: &'a Counter, pos: u32, } struct CounterIterMut<'a> { counter: &'a mut Counter, pos: u32, }

These track the position and hold a ref/mut ref to the original Counter.

Let us implement Iterator for both of these structs.

rustimpl<'a> Iterator for CounterIter<'a> { type Item = u32; fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> { if self.pos < 5 { let res = self.pos; self.pos += 1; Some(res) } else { None } } } impl<'a> Iterator for CounterIterMut<'a> { type Item = u32; fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> { if self.pos < 5 { let res = self.pos; self.pos += 1; Some(res) } else { None } } }

Note: We’re not using the counter field for logic (you could, if you stored state inside it). This just makes iter() and iter_mut() usable ergonomically.

Now the main part, the IntoIter trait.

rustimpl<'a> IntoIterator for &'a Counter { type Item = u32; type IntoIter = CounterIter<'a>; fn into_iter(self) -> Self::IntoIter { CounterIter { counter: self, pos: 0, } } } impl<'a> IntoIterator for &'a mut Counter { type Item = u32; type IntoIter = CounterIterMut<'a>; fn into_iter(self) -> Self::IntoIter { CounterIterMut { counter: self, pos: 0, } } }

That’s it.

If you noticed that the CounterIter and CounterIterMut implementations of Iterator are practically identical and that’s not a coincidence. Both structs:

-

Track an internal

posfield -

Don’t even use

counterfield in.next() -

Yield

u32values from 0 to 4, incrementingposeach time

The only difference? The reference type (&Counter vs &mut Counter), which we don’t actually mutate in .next()!

So why not DRY it ?

We could absolutely avoid duplication by using a generic internal iterator. This would be overkill for now, but it’s something the Rust standard library often does , use generic building blocks and type aliases to abstract out common behavior.

And that’s a wrap on iterators , from .next() to .iter_mut() and everything in between. We have seen how Rust's iteration model is both low-level and ergonomic, explicit yet elegant. Whether you're looping, lazily transforming, or crafting your own custom iterator, now you really know what’s going on under the hood.

Until next time!

Join the Discussion

Have thoughts or questions? Share them below. Your feedback helps improve future content.

Sign in with GitHub to comment